A tribute to Leonard Hoffmann (1959-1991)

- Nondiarist

- Apr 3, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2025

Leonard Hoffmann walked into my life on a Friday. Out of the blue.

On that day, my mother phoned me at work. This was only to be expected. My mother phoned me at work a lot. Her habit was to talk at me about stuff, never once displaying any inkling that she might suspect my attention was elsewhere while I went, “Mmm? Oh? Yes. No. Mmm. Really?” with the phone tucked under my chin. But this day she was unusually short of words. She seemed to be groping for them, in fact. This registered somewhere in a hidden compartment in my head and I started listening.

She’d had a call, she said, and we were going to have a guest for a few days – a surprise visitor Dad was going to pick up in town. I didn’t even get his name out of her. All I got was, “Helen knows him and gave him our address and number.”

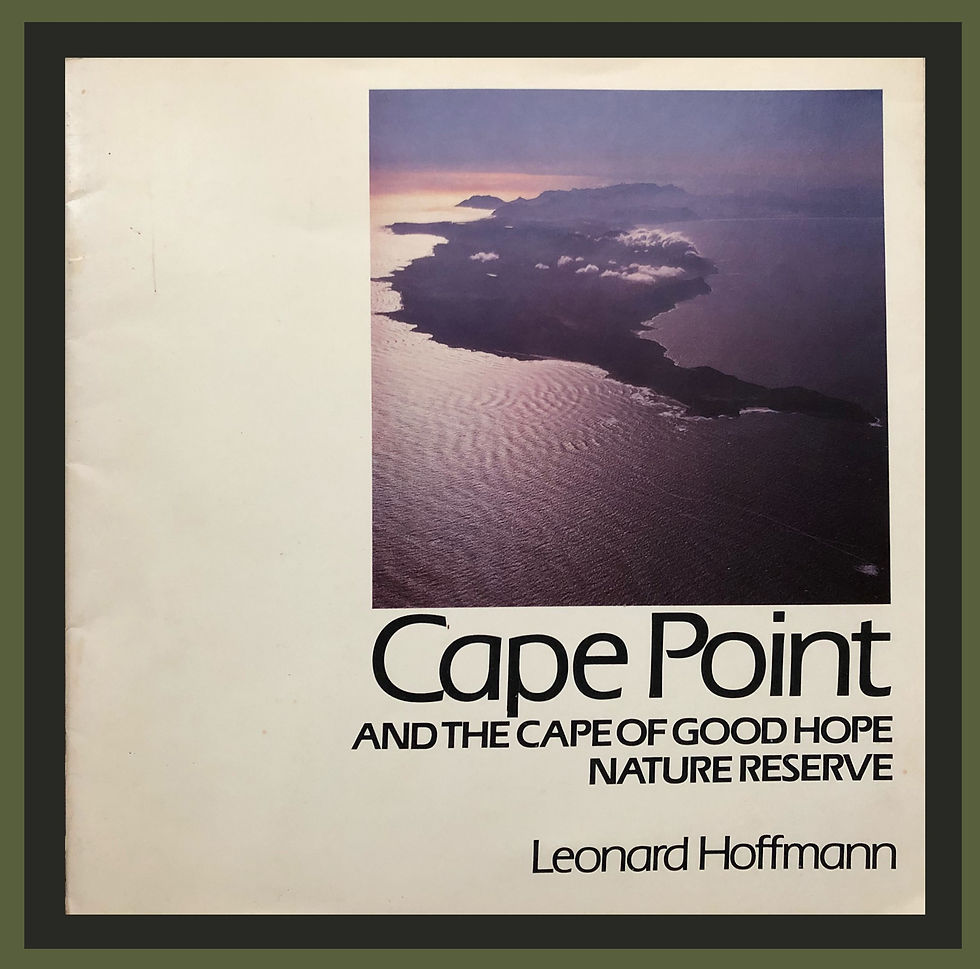

This, I supposed, was as good a recommendation as you could get. My godmother, Helen Wright, had been Mum’s first Bestie when they were six years old. Ever since I could remember, she’d lived with her husband, Gerald, on the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve where Gerald was the Chief Warden. I had a stock of cherished memories of the times I’d spent on the reserve, on that peninsula that's so representative of The Fairest Cape in All the World.

Thundering surf, rolling fynbos, barking baboons and my first ever experience of galloping a horse along a beach.

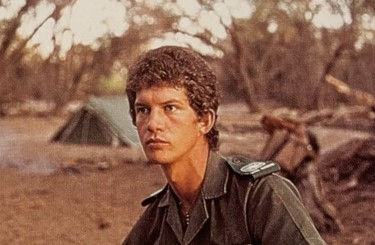

I got the full story when I arrived home. Our visitor had worked as a student ranger on the reserve along with Helen’s son, Mark, and he’d spent some time in, I think, Malawi, although my memory’s a bit hazy on that. He was hitch-hiking his way back to South Africa via Zimbabwe.

And so I met Mr Hoffmann.

He stayed for four days – a charming and considerate guest – and his passion for conservation and all things animal gave us an instant and unquestionable connection. It was the weekend, so I subjected him to a tour of Harare. I probably did a lot more talking than truly attentive driving requires but we survived it. There were obligatory ports of call on the itinerary – the botanical gardens, which I know he enjoyed, and the home of a friend who kept my horses for me, which I hope he enjoyed. He gave every sign of having a good time at least so I sincerely hope I reciprocated his entertaining and intriguing company.

On the Monday morning Dad took him back into Harare town centre and he continued his journey southwards. His parting words to me were, “Auf wiedersehen.” I remember thinking, “I will see him again.”

Here, I need to fill in a little about the background of this keen student of nature, wildlife photographer, herpetologist and author.

He was a stellar achiever from his school days. His prowess at chess took him to the South African Open Chess Championships, he was awarded the Toastmasters’ International Youth Leadership Programme Certificate and his athletic ability brought him the Wall’s Amateur Athletic Association Four Star Award. His period of National Service was spent in the South African Infantry Corps and during this time he qualified as a dog handler.

Before graduating with a BSc (Hons) Degree from the University of Cape Town, he spent time on the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve, which was where he met the Wright family and became good friends with Mark.

His dedication to his career as a nature conservationist and later as an expert in herpetology earned him much respect and admiration. He worked for the Department of Agriculture and Nature Conservation and the Desert Ecological Research Unit in Namibia and then returned to South Africa where he lectured in biology at the Owen Sithole College of Agriculture in KwaZulu. Here, he wrote his thesis for his University of Natal Masters Degree, “The Herpetofauna of the Owen Sithole College of Agriculture”.

He was awarded the MSc while working as a nature conservation scientist for the Department of Nature and Environmental Conservation (Cape Province) in both Stellenbosch and Grahamstown.

His photography work has been published in both South African and international magazines and he was a prolific author of technical papers, articles and bulletins on conservation in general and on the reptiles and amphibians of Southern Africa.

Mark Wright recalls that he loved his job and says how he enjoyed collaborating with Leonard on several projects, spending hours together capturing specimens of reptiles and frogs. He describes Leonard “a brilliant, slightly eccentric, caring, empathic, very capable conservationist, herpetologist and photographer. He had a unique, very proper way of communicating and a quirky sense of humour.” This sums up exactly the Leonard I knew.

And yet, behind all this, was someone I never knew. Someone who suffered severe depression that he was finally unable to overcome. When we met, there was so much to find out about each other’s interest in the animal kingdom that we never went much beyond this, and the complex politics of Africa, in our conversations and four days is a very short time.

Having said that, we corresponded for several years, but his letters were full of reports of his days at Etosha National Park, of his stimulating and fascinating field work with reptiles and of his writing and his research for his studies. He sent me newspaper clippings and photos and extracts of papers he had written and a signed copy of the book he published entitled ‘Cape Point and the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve’.

In it, he wrote, “Wendy, I trust that this little publication brings back fond memories of your visits to Cape Point”.

I never thought to ask and I never knew what was going on in the personal depths of his life or indeed anything about his childhood. Helen did tell us – and I don’t recall exactly when – that his father had committed suicide.

It was an act that Leonard was to tragically copy in 1991. Mark has filled in some more of the unhappy story for me recently. A very traumatic childhood can have a life-long effect. Leonard confided in Mark, who was troubled by the dark thoughts and numerous suicide references. Long periods of deep depression and convictions that he suffered from serious illnesses eventually led to him resigning from his post at the Department of Nature and Environmental Conservation and checking into a psychiatric hospital.

I was never aware of this, although I do recall that there was a long period during which I received no letters from him. I had moved to England by that stage and my address changed several times in a short time so I did not attach much significance to this. With compassionate help from friends, Leonard settled on a more even keel for a period, but it didn’t last.

It is one of my deepest regrets that, on a visit to South Africa just before I left Zimbabwe for good, I was unable to meet up with the guy who had made such a frustratingly brief entry into my life years before. Helen arranged for my mother and I to meet him at Mark’s home but on the day he sent a message to say he was not able to make it. I forget the reason now – I only remember being so bitterly disappointed that the whole ‘last-trip-round-South-Africa’ suddenly lost its sheen entirely.

Leonard enjoyed listening to The Police. I know this because my mother was extraordinarily ignorant of any music written after about the mid-sixties. She discovered a CD with the words ‘the police’ on the cover while she was vacuuming his room and speculated – I kid you not – that our guest was into brass band music.

Every Breath You Take is one of my all-time favourite songs. A few weeks before my wedding in September 1991, when I was driving home from work, the Wave 105 DJ played it. I sang along. Believe me when I say that I only ever sing when there’s no-one around to hear me.

Later that evening, my mother phoned me with the news that Leonard had taken his own life. He is buried in the Maitland Cemetery, near Cape Town.

His memory lives on.

Comments